Looking In

Zoom in… a little closer. That’s good. What do you see?

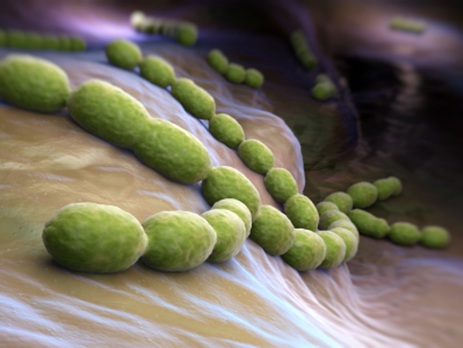

Streptococcus pneumoniae is in the midst of an invasion, thousands of tiny uneven spheres swarming in the warm, sickly yellow-green fluid that fills this middle ear (Sato, Liebeler, Quartey, Le & Giebink, 1999). It takes you just seconds to realize that these bacteria are multiplying by the minute. Everything- the eardrum to your left, the entrance to the Eustachian tube below you- looks red, swollen, irritated. You’re no doctor, but this condition looks uncomfortable at best.

Take a few steps back. Sitting in the chilly doctor’s office waiting room, a woman nervously taps her foot, glances at the door leading to the examination rooms, toys with a ring on her finger. You soon realize the reason for her unsettled disposition; a wail streams from the carriage beside her. The woman tries calming her baby, but that only seems to stir him more. You wager this whimper belongs to the child whose inner ear you have just viewed.

Ear Infections Around the World

This infected baby has unconsciously become a statistic, and one that continues to worry doctors today. While rates of occurrence have gone down in recent years, the unsettling truth is that most children will experience at least one episode of otitis media, or a middle ear infection, by the time they reach age three (Ramakrishnan, Sparks, & Berryhill, 2007). This makes it one of the most common pediatric infections in the world (Cheung et al., 2006; Reid et al., 2009). And with ever more bacteria becoming antibiotic-resistant, doctors’ worries are justified (Kyaw et al., 2006; Appelbaum, 1992).

(For more information on Otitis Media diagnosis rates in the US, please visit the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders)

Looking Back

Now pan across the globe until you find Minnesota- specifically, a modest research lab at the University of Minnesota. Wind back the clock to 1975. Step inside. A burst of wind almost knocks you over as you tug to open the heavy doors to the facility. Inside, your eyes take a moment to adjust to the dim lighting. A long hallway stretches out in front of you, with plastic plants and various office rooms and placards with foreign-sounding names lining the walls. Silence, save for the whirring of a distant air conditioner. Take a step forward and you notice a think glass door at the far end of the hallway labeled “Laboratory”. You walk up and peer inside.

The first thing you notice is – are those rabbits? – on one side of the room. Before you have time for another thought, you are taken aback by a muffled cheering sound coming from the other end of the room. A circle of men and women wearing university ID badges is formed around a table and a tall, bearded man in a dress shirt speaks to the group. You can sense the group’s excitement all the way from where you’re standing. From the looks on their faces, in fact, you would think that they had just made history…

These men and women had just made history. They discovered that if chinchillas were directly exposed to the bacteria that cause middle-ear infections (such as Streptococcus pneumoniae), the infection would remain in the animals’ middle-ears, making it possible now to track and study the microorganisms in a model similar to that of humans (Giebink, 1999).

For years, rats, mice, and even monkeys gave researchers some insight into how this infection behaved within animal models (“Chinchilla”, 2011); however, chinchillas stand out today as the only lab animals with similar enough ear structure to humans and in which otitis media can be easily produced by squirting very small amount of bacteria into the nose.

While these researchers at the Univeristy of Minnesota were not the first to use chinchillas as lab animals, they were the first to develop a method of studying otitis media in an amazingly close-to-human research model. This very same model would later help doctors with drug selection and dosing.

Looking Ahead

As with any other form of science, there is always room for improvement. Researchers today are searching for the ideal otitis media drug; this would be a drug that has an extensive antibacterial spectrum and high efficiency against resistant strains. Also, since otitis media can be caused by one of about three different strains of bacteria, an antibiotic that targets only specific strains is desirable to potentially increase the success rate of treatment (Cheung et al., 2006). The chinchilla model continues to help researchers help us.

In another part of the country, many years later, the sick baby has just recieved a prescription for an antibiotic called amoxicillin. This is a drug that the researchers back at the University of Minnesota had no idea about yet. The woman thanks the doctor with a huge smile, shakes his hand, and picks up her baby. Mother and child leave the waiting room with a piece of signed blue paper and not the faintest idea that they had forgotten to thank a few- no, they’re not rabbits- very important heroes of that day.

In Brief:

- Middle ear infections are one of the most common pediatric infections in the world.

- The chinchilla model provides an extremely accurate model with which to study ear infections.

- Improvements (such as development of a drug with a broad antibacterial spectrum) to existing treatments can be made with the help of the chinchilla model.

This article was written by cYw5. As always, before leaving a response to this article please view our Rules of Conduct. Thanks! -cYw Editorial Staff

Thank you for making this history from research to clinical practice so lively. Your story flowed beautifully in making the connections among these events, illustrating the necessity for animal research. Well done!

FASCINATING ANIMAL FACT: Only mammals have three bones inside their middle ear.

Pingback: Current Research: An “Evolutionary Glitch” | curiousYOUNGwriters